In her garden outside San Francisco, Deirdre Lehman tries to keep her demons at bay. For most of her life, medication and therapy have helped keep her depression under control.

“I’m technically bi-polar,” she said. “You can have episodes of the quiet time where the disease doesn’t appear.”

But when it does appear, for Lehman it’s like tumbling head-first into depression’s deepest abyss.

“I just drop off a cliff,” she said.

Clark, her husband, said one of the scariest episodes came back in 2018: “It wasn’t just depressed; it was suicidal, in a matter of hours.”

Deirdre recalled, “I said, ‘Clark, oh my God, the chatter is starting and I can feel it’s coming.’ This negative chatter about, ‘No one’s gonna love me. I’m ugly, I’m a burden. No one would miss me if I killed myself.'”

Correspondent Lee Cowan asked, “That’s what the chatter was telling you?”

“The chatter was telling me this.”

Clark hid all the knives, and all the pills, too.

She said, “You finally told my family, and then as each of them called, I said good-bye. I wanted to die.”

She was referred to Dr. Nolan Williams, the director of Stanford University’s Brain Stimulation Lab in Palo Alto, California.

“This is a brain emergency,” he said, “and we need to meet this with a really significant intervention.”

He was running a trial for an experimental treatment using targeted magnetic stimulation. It’s called SAINT, which stands for Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy.

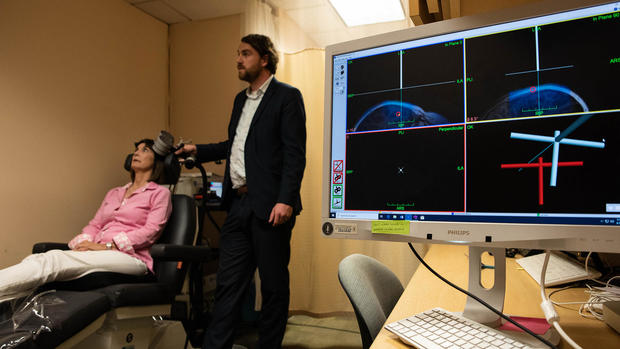

Applying the SAINT (Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy) treatment. STEVE FISCH/STANFORD MEDICINE

“We treat it like a brain disease,” Williams said. “We find the spot to stimulate the brain back into not being suicidal, not being depressed.”

In photos of Deirdre’s first SAINT treatments, just days after that suicidal crisis began, she went from a blank stare, to eating, to actually smiling, all in one day.

She said, “I had no chatter. None.”

According to Williams, “Within 24 hours, she was totally normal.”

“Were you surprised?” Cowan asked.

“Initially, I couldn’t believe it. And at some point, it just struck me that we’d found something that was really, really important.”

The American Journal of Psychiatry just published the findings of SAINT’s latest clinical trial: Almost 80% of the study’s participants saw their severe depression go into remission. Williams said, “It’s huge. It’s huge.”

One of Dr. Williams’ first patients was 83-year-old Merle Becker, who’s tried everything to relieve her depression: “Meds for more fingers than you have on your hand!” she laughed.

Becker described her depression as, “You feel that there’s no light in your life.”

Cowan asked, “And how long were you living that way?”

“It’s been there all my life. Since I was 20.”

She’s a therapist herself, specializing in depression, so she knows what she’s talking about. “Most people with a history of depression, particularly serious depression, feel a sense of shame,” she said. “This is something very deep inside. A heaviness in your body. You’re in a tunnel and there’s no way out.”

Her husband, Bill, has been by her side for 41 years, and he’s seen first-hand how SAINT makes Merle feel more in control.

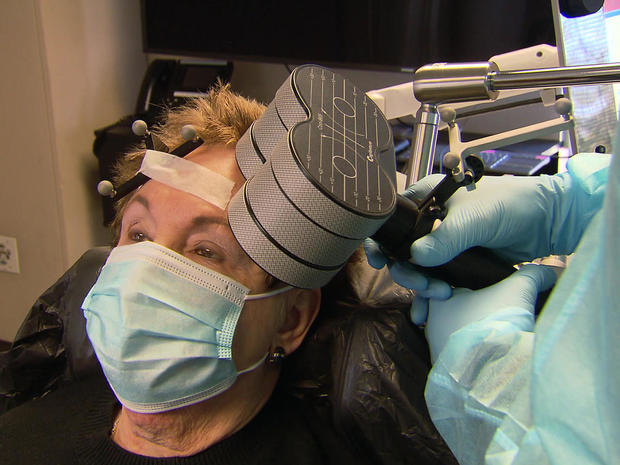

Merle Becker undergoes the SAINT treatment. CBS NEWS

SAINT builds on existing therapies for depression called Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, or TMS, but it uses a targeted and fast-acting approach. Dr. Williams uses an MRI to pinpoint the exact spot in Becker’s brain that is underactive in her depression and stimulate it with a magnetic coil.

“We’re trying to up-regulate or kind of buff-up the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex back to its normal state, so it has a sense of control,” Williams said.

“So, what you’re basically doing is, you’re telling this to turn that off?” asked Cowan.

“Yeah, that’s right.”

SAINT’S magnetic pulses are set to replicate the way the brain communicates with itself, and repetition of those pulses essentially teaches the brain how to maintain its balance.

Williams said, “All of a sudden they’re looking at you in the eyes; they’re smiling more spontaneously; and then by the end of the week, they are telling you they feel totally well and back to their normal self.”

It can be exhausting, and it’s rarely a one-time thing. Becker has been doing maintenance treatments periodically for the last four years … and so far, there have been no serious side effects.

“By the third day,” she smiled, “you feel better.”

WEB EXCLUSIVE: To hear one depression patient’s story of the SAINT experimental treatment, click on the video player below:

One depression patient’s experimental treatment by CBS Sunday Morning on YouTube

Now, there are two larger trials of SAINT underway, funded by the National Institutes of Health, including one that is testing SAINT in a hospital setting during a brain emergency, like a suicidal episode, where patients are under observation. “The scary statistic is, the highest likelihood of a subsequent suicide attempt or completion is in those months after the discharge,” said Williams.

He sees SAINT as something that hospitals could use as almost a fast-acting antidepressant, to stabilize suicidal patients who may, after a week of intensive treatments, leave the hospital feeling safe.

“It really changes not just numbers on a page, but kind of people’s perspective about their life, right?” he said. “They’ll turn around and say, ‘You know what? I feel totally differently about my depression now. I’m empowered.'”

Deirdre Lehman’s perspective became bright again. She went back to school to finish her college degree.

Cowan asked, “Do you feel depressed anymore?”

“No,” she replied.

“Not at all?”

“Not at all. Not at all.”

Williams said, “This intervention is something that has shown them that it’s really their brain. It’s not something about, you know, them personally, that deep self. But it’s really a brain disease that we can identify and really treat and move.”

For Merle Becker, it’s given her something she hasn’t had in a long, long while: “Hope. I hope the younger me is out there watching this.”

Recently, the FDA gave SAINT breakthrough status, which means it’s one step closer to becoming available.

Cowan asked, “So, where do you see this treatment going in five, ten years?”

“It will change the world,” said Lehman.

“That’s a big statement.”

“Oh, it’s a game-changer.”

Researchers generally don’t like to go too far out on the “game-changer” limb, but Dr. Williams hopes he’s inching closer every day: “It feels that it could be. It’s at a point now where I think we have enough data to say it looks real, you know? And if it does what we’ve seen in other folks’ hands, it very well could be.”

For more info:

- Brain Stimulation Lab, Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif.

- Photos courtesy of Steve Fisch/Stanford Medicine

Story produced by Deirdre Cohen. Editor: Ed Givnish.